My first class at The University of Iowa, in 1960, began at 8:00 AM. I aways arrived early for that

class after taking my wife to work, but there was always one person there ahead of me. That’s

how I got acquainted with John Knudsen. The class we waited for was Figure Drawing. We

often spent some time looking through and discussing each other’s sketchbooks.

John’s sketchbook drawings were basic ideas for future use, but they were powerful and useful

ideas. His drawings from studio models were excellent studies of form and composition. He

obviously enjoyed drawing, and I remember describing them to my wife as being the strongest

student work in that early morning class.

We had several classes together during each semester, and it was always clear that he felt

comfortable majoring in painting with Eugene Ludens and printmaking with Mauricio Lasansky. I

thought that he had a natural talent for printmaking and often encouraged him to concentrate on

copperplate engraving. He was good at it and enjoyed it. But his technical virtuosity for

engraving seemed to present a problem for him, since he despised anything that appeared to

be “flashy”, a pejorative term that he often used to describe work that conveyed too much

technical brilliance, but not enough thought and feeling. His work was never just “flashy”.

The ideas of S.W. Hayter had long been a strong influence on artists of many cultures at that

time in the early ’60s. John was favorably impressed by the famous artists and works that came

out of Hayter’s Atelier 17 in New York and Paris. Several of our fellow classmates had either

studied with Hayter or were making their plans to follow in the footsteps of Maestro Lasansky to

travel to Atelier 17. John set his sights on going to Paris someday to study with Hayter.

Our good friends were two graduate assistants in printmaking, Virginia Myers and Jack Orman.

Both had traveled extensively to European museums and galleries. Their experiences and

advice influenced John’s future travel decisions.

Stretching canvas for painting was a time-consuming project, so we worked together on building

stretchers and sizing canvas at his home in West Branch, Iowa. John and Karin’s first home in

Iowa City was a University-owned quonset hut, but they later moved to West Branch. We both

owned VW Bugs which were about the only vehicles getting around in the snow-covered hills of

Iowa City.

John loved the prints of the Northern Renaissance and worked on his MA Thesis under Charles

D. Cuttler, who was our professor in Northern Renaissance Art.

John was a regular subscriber to the print catalogs published twice a year by Craddoch and

Barnard in London, and he often ordered prints to add to his private collection. I also

subscribed, and whenever the latest catalogs arrived, we would spend a few hours doing our

research in the Art Library before sending in our own orders.

We were both struggling amateur guitarists, trying to make music in our spare time.

Hootenannies were held often at the Student Union, packed with students and performers. We

occasionally attended, but neither of us stepped forward to perform. At that time, most students

in the Hootenannies were performing songs made popular by Burl Ives; The Kingston Trio;

Peter Paul & Mary; Joan Baez; Pete Seeger; and Bob Dylan.

It was a time of rioting in Alabama, parts of The South, and other parts of the country. The most

popular songs on campus were songs of protest and labor unions. We were kept abreast of the

local activities by our academic advisor, Norval Tucker, who was an activist.

Every student of Maestro Lasansky’s was required to draw 25 self-portraits and to go to the

museum in MacBride Hall to make drawings from mounted taxidermy specimens. The Maestro

also instilled in his students an interest in the engineering involved in every etching press. After

a major flood in 1962, Maestro Lasansky hired John and I to disassemble and crate three

flooded lithography presses (Grant Woods’ presses) and move them to other locations while

mud was being cleaned up.

Part of the student routine was to spend the noon hour playing volleyball. We stretched a net on

the river bank outside of the print studios. As winter approached, the number of players went

down with the temperature, but John and I were determined to keep the routine exercise going.

Eventually, the temperature hit a record low of -35 degrees. We were the only players crazy

enough to stretch the net and play volleyball — a very short match.

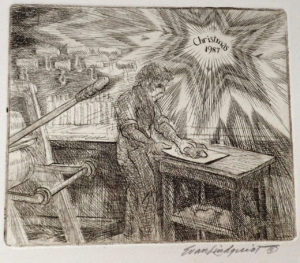

John loved to experiment with his work. One experiment was an engraving that he engraved

into a sheet of brass, a difficult metal to engrave, but he did a superb job. Since brass is

expensive, he turned the plate over and engraved another image on the other side of the sheet.

He editioned both sides of the plate — two of my favorite images by John.

In these memories from 57 years ago, I still hear a good-natured chuckle from our talks about

various family customs formed by our similar ethnicities going back many generations. I can still

see John with a quiet smile while discussing current events, philosophy, and politics.

Evan Lindquist, Artist-Printmaker, Retired Professor of Printmaking and Drawing at the University of Arkansas,

First Artist Laureate for the State of Arkansas